By Nick Fisher, Portfolio Manager

I recently read the autobiography of Sam Zell, an extremely successful real estate investor known for his uncanny ability to buy low and sell high. In the book he tells the story of his father’s foresight and decisive action that preserved his family in Pre-world-war-2 Poland. As a successful grain merchant, his father kept apprised of political and social happenings in Europe through his extensive travel and interest in short wave radio. While some people looked at this “hobby” of international politics as a complete waste of time, it gave his father a unique outlook on the world. With this perspective, coupled with decisive action, the Zell’s were able to start a successful new life in the United States.

This story really highlights the importance of managing risk and the preparation and psychology that influences so many people. While we have no interest in calling a top in the stock market, we are interested in helping our clients be prepared for whatever opportunity or calamity that comes our way. While some of these can be issues that may have a grand impact, other issues may be more subtle over time.

One such issue which will have a dramatic impact to portfolios over time is the high price (valuation) of US stocks. We have recently discussed the opportunity that emerging and international markets present compared to the US markets. By making some sensible assumptions, we can actually predict (with reasonable accuracy) what 10 year returns will look like in the US, International and Emerging Markets.

The great John Bogle (founder of Vanguard Group) is predicting a 4% return in the US stock market. His public reasoning breaks down the components of return into the 3 basic categories: earnings growth, dividends and the expansion or contraction of valuations. His math is as follows:

Other well seasoned investors such as Jeremy Grantham are predicting a near 0% return in the US stock market.

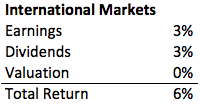

International and emerging markets are much more attractive given the lower valuations. If in John Bogle’s formula we can add 1-2% of positive return due to valuation expansion, this makes for a more attractive return. 2-5% of additional return annually over the next 10 years, while not guaranteed, is nothing to scoff at.

Underweighting US stocks and overweighting international and emerging markets has its tradeoffs. In order to achieve this additional return, we must be able to weather the additional volatility associated with international and emerging markets. Over the last three years, emerging markets have had 60% more volatility with a standard deviation of roughly 16% compared to 10% for US Large Cap stocks (iShares EEM compared to IVV ETF). In hindsight, of course emerging markets are more volatile than US Large Caps, but we can’t accurately forecast what future volatility will be (it will surely be more than what we have experienced recently though). Under current conditions we believe that the additional return more than compensates us for the additional volatility given a long time horizon.

Index A or Index B

The active vs. passive conversation has become quite the rallying cry of late for passive investment managers. The argument starts with the fact that the vast majority of mutual fund managers have not managed to beat the markets over the long-term.[1] The passive manager believes it is better to just buy a passively managed index ETF and forgo the expensive fees associated with hiring a manager/management team to allocate their investments.

If you feel like we’ve been here before, you’re not mistaken. Doesn’t this sound like 2007 all over again? Or 1999? Or 1987? Or…you get the idea. “Just own the market – it’s all good. This time is different.”

We absolutely agree that it is important to keep investment management fees reasonable (as it is with financial planning, tax preparation, legal and any other professional fee for that matter). But never at the sacrifice of quality advice and wisdom. There are times to be frugal and there are times to pay for quality advice. Frugality can be a virtue, but in these uncertain times some investors are going to be disappointed.

The idea that one can choose a single index or group of indexes without making a significant active decision regarding risk/reward is perplexing. The mere choice of indexes or ETFs is a meaningful decision regarding the future prospects of the portfolio. We believe today’s environment offers plenty of examples of this.

Consider two indexes either one of which could appear in someone’s portfolio of long-term investments meant for retirement.

Obviously the valuations on investment B are quite rich compared to investment A. It is no wonder that so far this year investment A is outperforming investment B. Yet investors continue to pile into investment B. By now you may have guessed that investment B is the US stock market. It is priced to perfection and in a best-case scenario you are likely to achieve below average returns over the next 10 years (unless you can time the market and get out at the top - a fools errand). In fact, the United States is the most expensive stock market in the world according to Star Capital.

Investment A, which is South Korea, is one of the more attractive international markets in the world. Buying what is cheap has consistently increased the odds of average to above average returns over 10 year periods compared to buying the most expensive stocks. Of course, a portfolio should consist of a diversified allocation of less expensive international stocks. But we gladly welcome volatility risk from international markets in exchange for the long-term valuation risk posed by an overexposure to the United States.

In long-term portfolios we will continue to make steady shifts to avoid the most expensive stocks and markets and allocate ourselves to the least expensive. This is in our DNA as investors. We are active managers that seek value when others cannot or do not.

[1] We take exception to this argument, as there are many subtle and not so subtle nuances to this conversation. There is quite a subset of high performing mutual fund managers with similar characteristics that seem to outperform over long periods, but this doesn’t fit with the passive narrative so the proponents tend to conveniently leave it out of their marketing message.